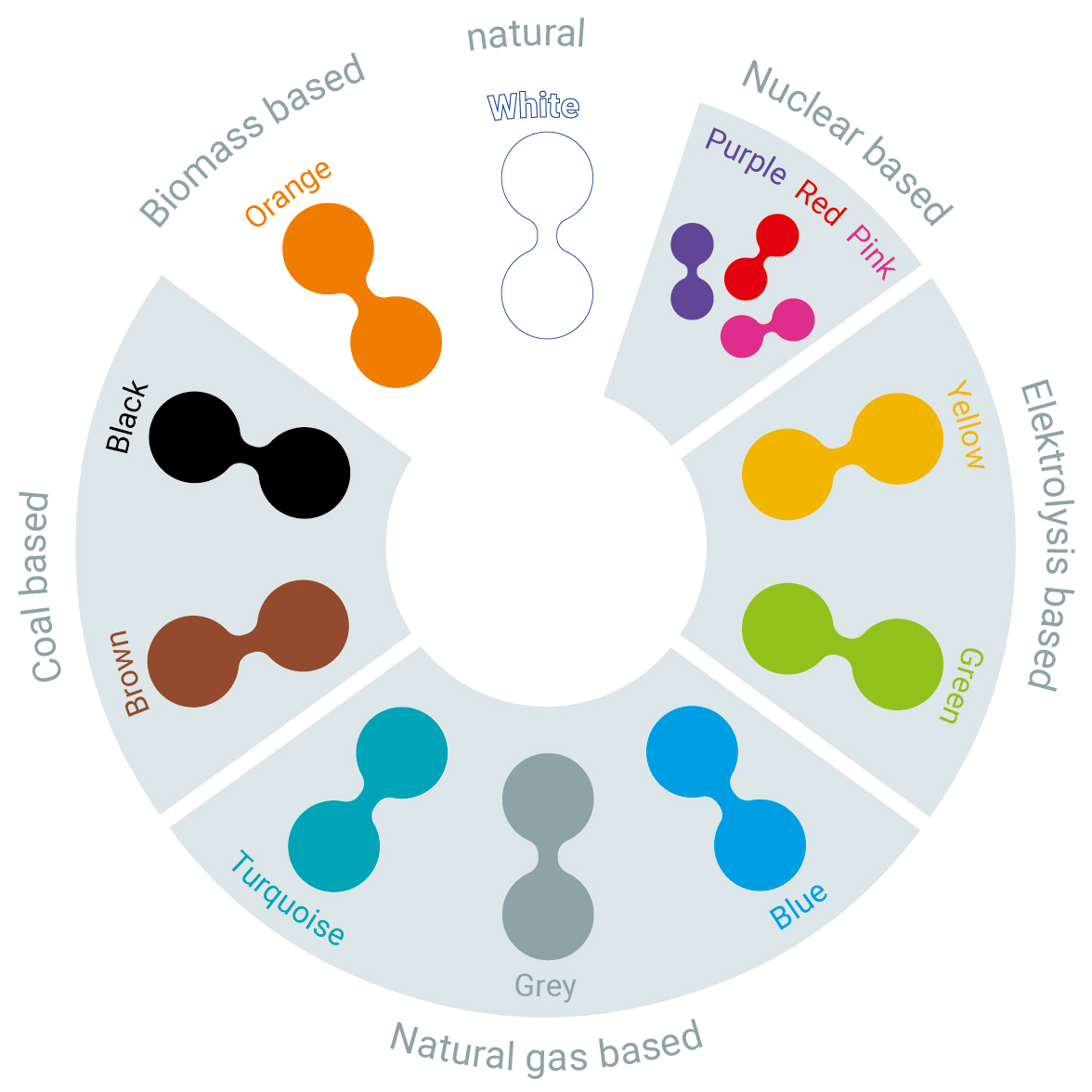

Hydrogen is a colourless gas. Yet when people talk about the colours of hydrogen, they mean the way it is produced – and how climate-friendly that process is. One hydrogen colour ought to be straightforward, and yet it is strangely unclear. Orange hydrogen is defined in different ways. The artificial writing intelligence ChatGPT offers the following definition: “Orange hydrogen is a category in the colour classification of hydrogen that refers to production from biomass or waste. It is produced through thermochemical gasification or pyrolysis of biogenic feedstocks. This method can be climate-friendly if sustainable biomass is used, as the carbon dioxide (CO₂) released during combustion was previously absorbed by plants.”

Orange hydrogen is therefore green when the carbon used is biogenic – that is, derived from living organisms or, in geological terms, ones that died only recently. Such carbon can be naturally degraded and returned to the atmosphere as part of the short-term carbon cycle. Carbon can also circulate in the long-term cycle, for example in sediments or fossil fuels such as coal and oil. This carbon only enters the atmosphere during natural disasters such as volcanic eruptions – or because humans burn it. The latter is the main cause of current global warming.

A Question of Cycles

From a climate perspective, the CO₂ balance of biogenic carbon is, at best, a zero-sum game – in other words, climate-neutral. The CO₂ emitted has previously been taken up in the short-term cycle. If the carbon originated in the long-term cycle – as in coal or oil – then the CO₂ balance of orange hydrogen is no longer neutral, because this carbon increases the atmospheric concentration beyond natural levels. This can apply to the thermochemical processing of waste, for example plastics produced from fossil carbon that cannot be biologically degraded.

“Orange hydrogen is green hydrogen for me if the waste it is produced from is based on biomass. But there are also waste streams where we should really be talking about fossil-based hydrogen. That is why the term orange hydrogen is somewhat confusing, and you need to look closely at the composition of the waste.”

Andreas Peschel explains that producing orange hydrogen comes with an extra task. This makes orange hydrogen a specialist topic – but one that can be relevant for certain niches. “If we take biomass-based waste as a starting point, then we need to consider what we do with the carbon fraction,” explains Andreas Peschel. It is not only important to prevent carbon from being released into the atmosphere in the form of CO₂ – it is also a valuable chemical resource.

Green Fuel

“Instead of producing orange hydrogen, we can use this feedstock more sensibly to create carbon-based molecules: that is, compounds of hydrogen and carbon – so-called hydrogen derivatives such as dimethyl ether, ethanol or methanol. These offer meaningful applications, for example as fuels for agricultural machinery or for the chemical industry,” says Andreas Peschel. There are good regional links for such orange derivatives. In the Rhenish mining area, agriculture and the bioeconomy are both strongly represented. It is also possible to convert the biomass into hydrogen and either store the carbon or recover it as solid carbon (biochar).

For the potential of hydrogen production from biomass, however, there is a limiting factor, as Andreas Peschel explains: “For much of the available biomass, there are better value-creation pathways. Take sugar production: the beet is processed into sugar.” The remaining biomass is often turned into beet chips to feed cattle. These contain valuable substances that have a higher value than converting them into hydrogen in a biogas reactor. If this source of feed were removed, replacement crops would have to be grown – which increases costs. “Most of the time, there are already good uses and thus a value chain for this biomass. And those uses usually make more sense than producing electricity or hydrogen from it.”

It is only worthwhile for genuine residual materials that are currently incinerated. Regardless of that, there are energy sources far better suited for hydrogen production: solar and wind energy. Which brings us back to green hydrogen – produced using green electricity.

The copyright for the images used on this website is held by Forschungszentrum Jülich, aligator kommunikation GmbH and

stock.adobe.com.