It is almost exactly 130 years since Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen discovered something he had not been looking for at all: X-rays. Just a few weeks later, he produced the first X-ray image in human history – showing the bones of his wife Anna Bertha’s hand, complete with her wedding ring. In 1901 he received the first-ever Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery.

X-rays not only allow doctors to see broken bones and help security staff scan luggage at airports. They are also a perfect tool for satisfying the desire that drives Goethe’s Faust: “that I may perceive whatever holds the world together in its inmost folds”.

Making the Atomic Scale Visible

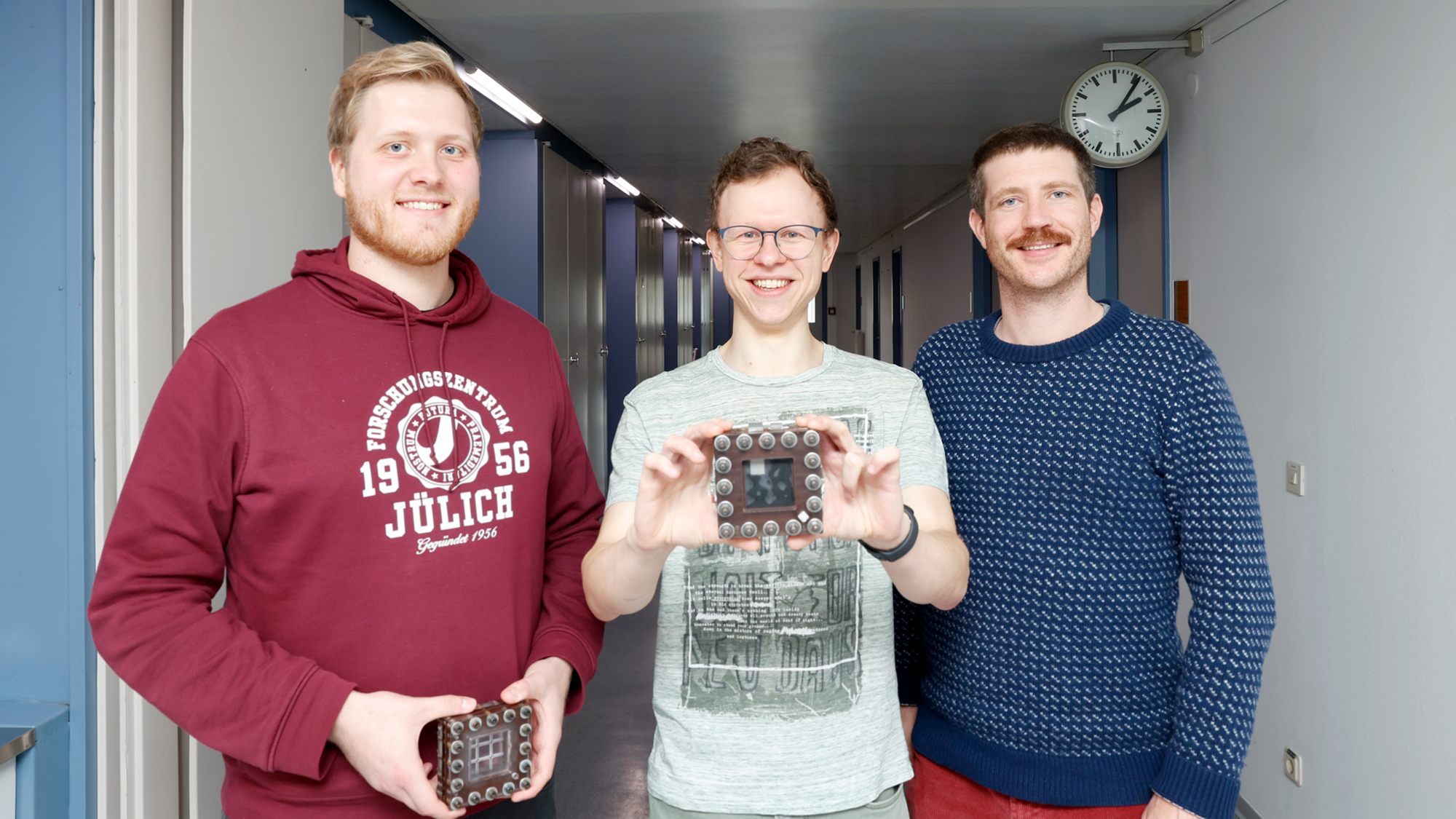

“X-rays are ideal for understanding what happens on the molecular and atomic levels,” says Dr Peter Walter, Head of Department at the Institute for a Sustainable Hydrogen Economy (INW) in Jülich, where he is establishing an X-ray laboratory for the INW-1 research area, Catalytic Interfaces. Under the leadership of Prof Hans-Georg Steinrück, INW-1 investigates what takes place at these interfaces. “X-rays have exactly the right wavelength to show whether anything has changed on the molecular or atomic scale. And they do not destroy the structures we illuminate with them,” Peter Walter explains.

“X-rays are ideal for understanding what happens at the molecular and atomic level.”

Dr. Peter Walter, Head of Department at the Institute for Sustainable Hydrogen Economy (INW-1), Forschungszentrum Jülich

Matchmakers and Divorce Lawyers

The “magic” of heterogeneous catalysis takes place at the catalytic interface. Heterogeneous means that the catalyst is a solid that can be separated and reused, while the reactants – such as hydrogen (H₂) and nitrogen (N₂) – are gases. The interface is the contact zone between catalysts and reactants. This is where molecules attach, their bonds loosen or rearrange, and reactions occur more quickly or at lower temperatures.

This is important for making hard-to-store hydrogen more manageable, for instance by reacting it with nitrogen to form ammonia (NH₃). Hydrogen in its natural form has a very large volume; the same amount stored as ammonia has a volume 1,300 to 1,500 times smaller. To “marry” nitrogen and hydrogen, a metallic catalyst is required. Prof Regina Palkovits, who heads the INW-2 research division Catalyst Materials in Jülich, calls catalysts the “matchmakers and divorce lawyers of molecules”.

INW-1 wants to understand more precisely what happens during this “magic” between the molecules of hydrogen, nitrogen, and the catalyst. Researchers there ask, for example, how the reaction can be accelerated or intensified – or slowed down if it becomes too vigorous. “Why does a catalyst lose its activity, and what can we do about it?” says Dr Jimun Yoo, team leader at INW-1, describing one of the central questions. If a reactant lies flat on the interface and blocks more binding sites than if it were standing upright, the question arises how this could be changed.

X-rays, whose wavelength is roughly the size of a hydrogen atom, show whether the atom’s position has shifted – because such a shift alters the reflection angle of the rays. A so-called beamline can measure this. Such a laboratory is now being developed in Jülich.

“We need to detect the tiniest changes,” says Jimun Yoo – currently at synchrotron facilities in Hamburg or Grenoble, and in future also in the institute’s own X-ray lab. A synchrotron, a particle accelerator with an extremely bright light source, delivers a high flux of photons for high-resolution snapshots of catalytic interfaces. Photons are the massless building blocks of light that carry energy. Beam time at a synchrotron is free for academic research, but limited. “It’s perfectly suited to us because it allows us to take a high-resolution snapshot of the catalytic interface,” Jimun Yoo explains.

Piecing Together the Picture

Synchrotron time must be used efficiently. The new X-ray laboratory, once operational, will help prepare those experiments. “We need more time to generate a single image, because our source emits fewer photons than a synchrotron. That enables us to perform long-term studies, helping us better understand how we can make catalysts more durable,” says Jimun Yoo. Both time scales matter: long-term observation and instantaneous snapshots. “You never get the full picture from a single experiment – only by combining the data.”

It will take some time until the new beamline in Jülich is completed. “Once it is in place, we will have capabilities that are very rare outside large research facilities such as a synchrotron,” Peter Walter notes. One instrument already available at the research centre is a multifunctional X-ray diffractometer – essentially the Swiss Army knife of research X-ray devices. It supports many measurement methods but does not reach the resolution of a synchrotron. The latter fires as many photons in 0.4 seconds as a diffractometer does in 20 minutes. The effect: instead of a detailed snapshot, it provides insight into how structures change during the reaction. “This already gives us valuable data on the reaction at the interface – and it takes us a significant step forward,” says Hans-Georg Steinrück.

The copyright for the images used on this website is held by Forschungszentrum Jülich, aligator kommunikation GmbH and stock.adobe.com.