We regularly receive many questions on the topics of water, structural change and the Rhineland mining region. Our founding director, Prof. Peter Wasserscheid, provides a few answers.

hydrogen

When will hydrogen be able to power my home?

Probably not at first. Currently, and for the foreseeable future, there are technologies that are better suited to the needs of a household. Supplying a single household with hydrogen is expensive because the storage technology is too powerful in relation to consumption. Hydrogen could theoretically make sense if large neighbourhoods were to be supplied. However, there are significant obstacles here too. All consumers would have to switch to a hydrogen-compatible system at the same time, which is not realistic in practice. It would be conceivable to plan a new large neighbourhood with a hydrogen supply. However, given the current levels of efficiency and effectiveness, heat pumps and photovoltaic systems on roofs are also more suitable here.

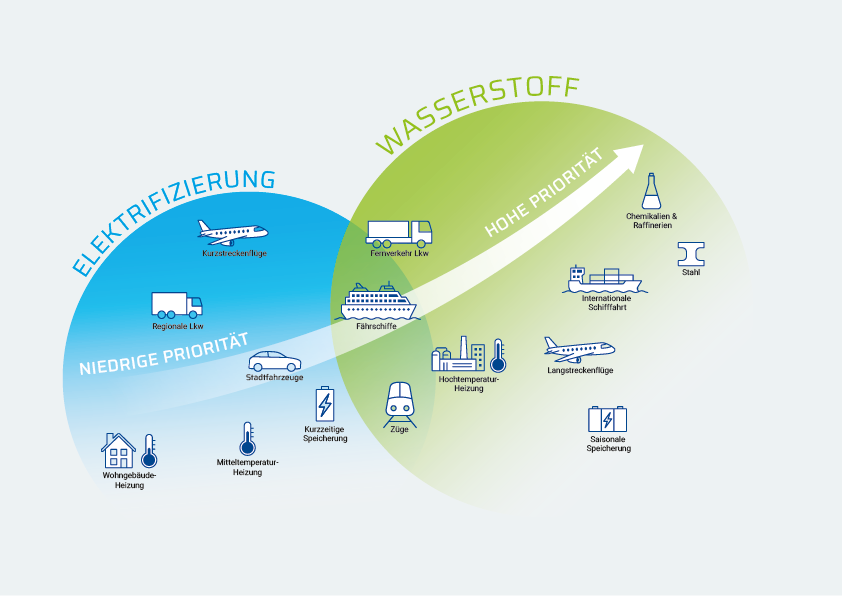

In which areas is hydrogen the only option? In which areas does it make sense?

There is a rough rule of thumb: the higher, more constant and longer-term the energy demand, the better hydrogen is suited. For example, there is no alternative to hydrogen in the production of green steel, for large ships and as long-term storage to secure supply in the future when too little renewable energy is produced.

There are other sectors in which hydrogen and battery storage complement each other well. For most drivers who travel long distances on average every day, a battery-powered electric car will be the best choice in the future. This is especially true if they can obtain the electricity from their own photovoltaic system. For people who regularly travel very long distances and for whom the time lost charging the battery outweighs the additional cost of hydrogen, a hydrogen car can make perfect sense. The prerequisite is that the routes travelled are supplied with hydrogen filling stations. In Germany, there are around 110 filling stations (86 open, 25 under construction, to be completed by November, so please revert to 86 if this article is published online before then) that provide good coverage of metropolitan areas.

structural change

What is that?

The term structural change refers to changes in the economic, social or political structure of a society or region. Structural change in the Rhineland mining area is the result of the phase-out of lignite-fired power generation, which has been the economic backbone of the region for decades. In 2023, the state government of North Rhine-Westphalia decided that lignite mining in the Rhineland lignite mining area will come to an end by 2030.

What is the goal?

The structural change in the Rhineland mining region has two objectives: the energy transition away from lignite as an energy source towards a climate-friendly energy system, and the creation of new jobs in the expansion of renewable energies to counterbalance the jobs lost in lignite mining.

The Rhenish mining area

What is the Rhineland mining area?

The Rhineland mining area covers a good 5,200 square kilometres on the left bank of the Rhine around the active and former opencast mines and power plant sites. It consists of the districts of Heinsberg, Düren, Euskirchen, the Rhine district of Neuss, the Rhine-Erft district, the city region of Aachen and the cities of Aachen and Mönchengladbach. A total of 2.5 million people live in the Rhineland mining area. The Rhineland mining area is the largest lignite mining area in Europe. Of the total of 38 billion euros that the federal government is providing for the five lignite mining areas until 2038 as part of the 2020 Structural Strengthening Act, 14.8 billion euros will go to the Rhineland mining area. The money is to be used to fund projects that generate new economic power and new energy security.

How far have we already come in structural change?

INW founding director Peter Wasserscheid puts it this way: ‘The field has been prepared, the plants are already sprouting from the ground. But it’s still too early to harvest.’ Most of the new jobs that are being targeted have not yet been created. But it is now becoming apparent that the transformation is gaining momentum. More and more construction projects are springing up. Software giant Microsoft has announced billion-dollar investments in data centres for artificial intelligence, which will be built in the Rhineland region. Taiwanese computer company Quanta Computer Inc. will move into Jülich’s Brainergy Park next year. Operations at the new site are scheduled to start in 2025 with around 90 employees. There are firm plans for rapid growth to 480 jobs, with up to 1,000 planned in the medium term.

Our institute started at the end of 2021 with the award of funding and two employees. Around 80 people now work at the Institute for Sustainable Hydrogen Economy (INW). The first technical hall is in operation and further expansion measures are planned. The INW forms the core of the Helmholtz Hydrogen Cluster (HC-H2), which also includes other project partners from industry, research and administration. The aim of HC-H2 is to generate new value in the Rhineland region in the coming years. This means that new jobs will be created in collaboration with the project partners.

The copyright for the images used on this website is held by Forschungszentrum Jülich, aligator kommunikation GmbH and

stock.adobe.com.