What do we need hydrogen for?

The non-fossil energy system of the future will require green electrons that flow through power lines and can be stored for short periods in battery systems. But it will also require green molecules that can store and transport large amounts of energy over very long periods, as well as enable material value chains, for example in the chemical or metal-processing industries. All green molecules are connected to green hydrogen in some way. Either hydrogen itself is used or so-called hydrogen derivatives. These are energy-rich compounds created by reacting hydrogen with suitable carrier molecules. In the form of hydrogen derivatives, hydrogen becomes easier to handle, for example within the existing infrastructure for liquid fuels. There is a simple rule of thumb: the longer the intended energy storage period and the higher the energy demand of an application, the more hydrogen and its derivatives come into their own.

Where does hydrogen come from?

In future, partly from domestic production, but for the most part from imports. The German Federal Government’s hydrogen strategy estimates the 2030 demand for climate-friendly hydrogen at 95 to 130 terawatt hours (TWh). Around 28 TWh are expected to come from German production in 2030 – meaning that three-quarters would need to be imported. Despite the very strict rules for green hydrogen, its share is expected to increase significantly over the coming years. According to the Northwest European Hydrogen Monitor 2025, around 28 TWh could be green by 2030, a significant portion of it from imports. To classify hydrogen as green, it is not sufficient simply to use green electricity in an electrolyser. The electricity must also be generated in a newly installed production facility at the same hour it is consumed.

Is imported hydrogen more expensive?

Highly likely, imported hydrogen is not more expensive – otherwise there would be no economic basis for importing it. We need imports to meet our demand, and at the same time we see clear cost advantages in obtaining cheaper hydrogen via imports. The cost benefits arise from the fact that countries with vast land areas and high levels of sunshine and wind can generate renewable electricity far more cheaply than we can here in NRW. At the best wind locations in the world, the same turbine produces roughly twice as much electricity as in NRW. Imported hydrogen captures this advantage. Higher electricity yields per installed system and lower installation costs can therefore more than offset transport costs in the long run. History shows: Germany has always consumed more energy than it can produce. Imports are therefore not a problem but a tradition – and part of our energy security. Transported energy molecules are stored energy, meaning they also serve as protection against dark doldrums or other disruptions to energy supply.

Is hydrogen competitive?

Hydrogen is competitive. Today already in numerous specialised applications, and in future certainly in much broader use – namely wherever battery solutions are unwieldy or expensive. And of course in all areas where the material properties of hydrogen are required. We must not forget: hydrogen technologies have not yet experienced the scaling effects that dramatically reduce costs and drive rapid technological progress. Solar panels and batteries were also extremely expensive before mass industrial production began. We must therefore avoid repeating the pattern in which large-scale deployment only begins once Chinese suppliers bring substantially cheaper hydrogen components onto the European market. That was the case with photovoltaics and batteries – and the result is that the overwhelming majority of batteries and solar modules are no longer manufactured in Germany. We should not allow this to happen again with hydrogen.

Which applications make sense first?

Anything that is at least potentially economical makes sense – even without permanent subsidies or excessive regulation. This straightforward view reflects the nature of the problem we want to solve. The issue is climate protection, and that requires global change. It is a fact that the strongest driver of change is economic benefit. Research and development should therefore aim to make sustainable products and technologies so good and so affordable that they become attractive purely for economic reasons. Only then will we see global uptake and meaningful climate benefits. How do we get there with hydrogen? We need to start with today’s technologies and focus first on applications where economic viability is already present or where the gap between current costs and the economic value of using hydrogen is particularly small. These are the areas where scaling effects and ongoing technological improvements can most quickly deliver economic advantages. Every commercially successful application supports market growth, motivates further technology development, reduces costs, and enables additional applications. We should under no circumstances begin where economic viability is nowhere in sight.

Where can we expect progress?

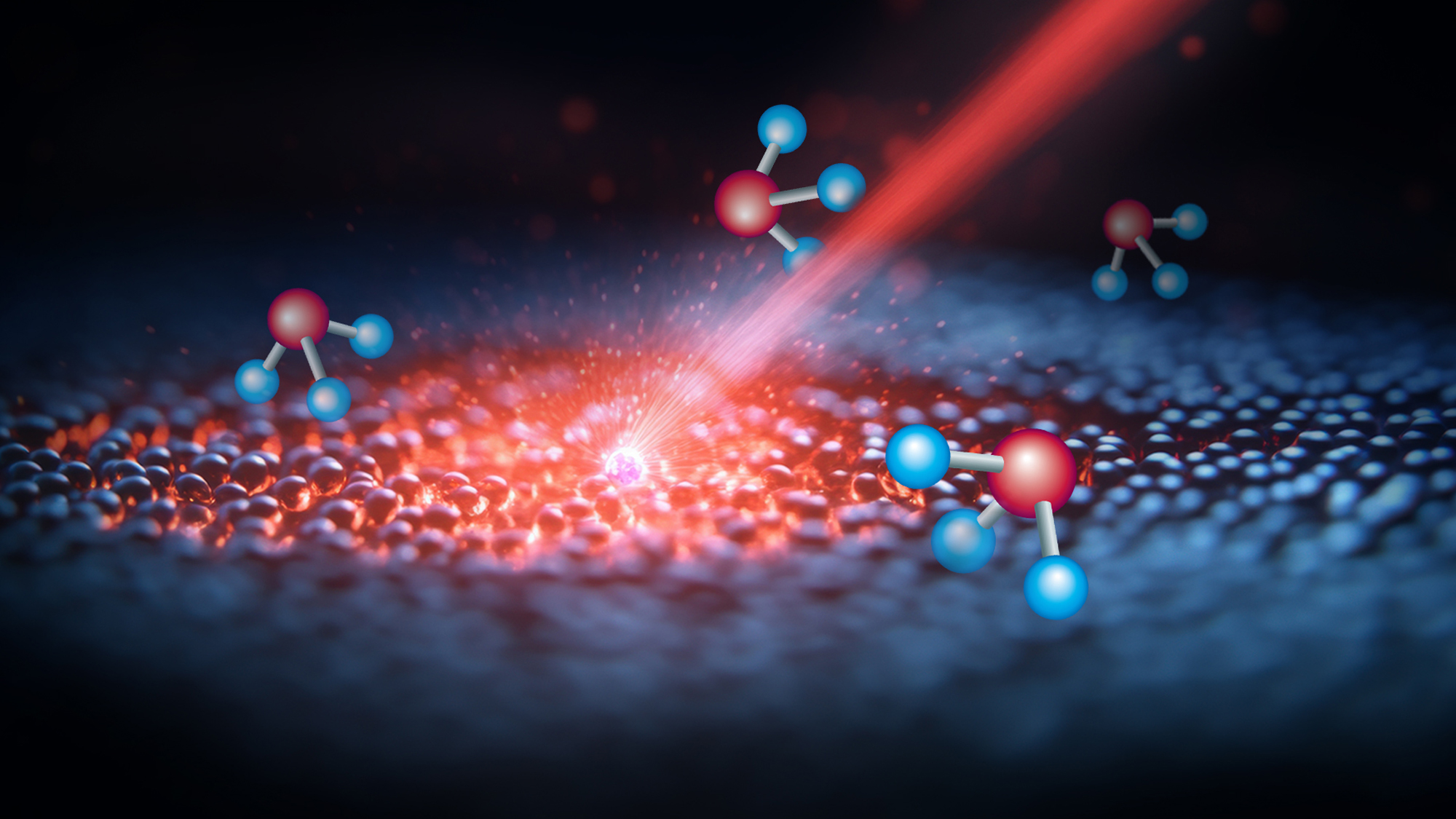

Prof. Peter Wasserscheid compares many hydrogen technologies today to the state of the automobile in 1910 – the technical principles have been demonstrated, but most of the benefits of series production have yet to materialise. Things are, however, moving: electrolysers and fuel cells are becoming more efficient. New catalysts for hydrogen production, storage and reconversion use rare metals far more efficiently or replace them with cheaper materials (page 8). Large-scale industrial processes for producing the chemicals and hydrogen carriers ammonia and methanol (page 10) are also being adapted: instead of constant natural gas supply, future systems will need to work with green hydrogen that is available depending on wind and solar conditions. New load-flexible reactors can respond to these fluctuations, helping reduce production costs for green ammonia and methanol.

The copyright for the images used on this website is held by Forschungszentrum Jülich, aligator kommunikation GmbH and stock.adobe.com.