Everyday questions about hydrogen – answered by researchers from the Institute of Climate and Energy Systems (ICE) and the Institute of Energy Technologies (IET) at Forschungszentrum Jülich.

Is hydrogen a climate killer?

Martin Riese: “The fact is that hydrogen has three negative effects on the climate. If it is released into the atmosphere, the lifetime of methane there is increased, and the climate gas ozone in the upper troposphere and climate-damaging water vapor in the stratosphere also increase. If we look at the future global hydrogen economy, the decisive factor will be how much hydrogen will be lost here – through leaks, for example. Current studies estimate these losses at between one and ten percent. But even at ten percent, the large-scale switch to hydrogen would be a clear benefit for the climate. This is because the large amount of CO2 that would be saved would cause much greater damage to the climate. However, the positive effect would be weakened. In order to determine the specific effects of H2, we will include hydrogen in our balloon measurements in the atmosphere in future.”

Prof. Martin Riese, Stratosphere (ICE-4), Forschungszentrum Jülich

Will we soon be able to heat our homes with hydrogen?

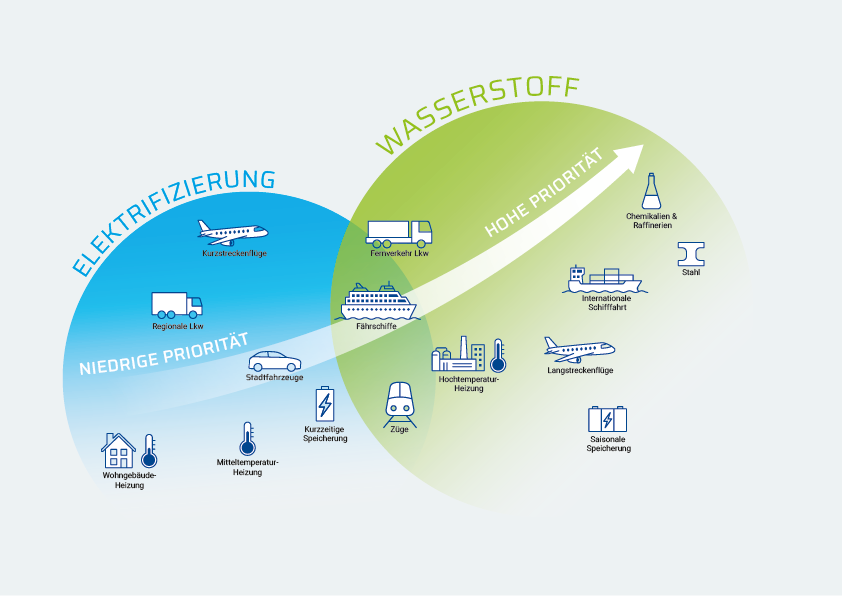

Noah Pflugradt: “They already exist: gas heating systems that are “H2-ready”, i.e. can be converted to burn hydrogen. There are certainly future scenarios and places where these could be useful. However, until hydrogen is produced economically on a large scale and also reaches the end consumer at a reasonable price, it will not be economical. To protect the climate with hydrogen for heating, we need green hydrogen produced with electricity from renewable energy sources. H2-ready systems as a heating alternative are therefore currently a bet on a development that I cannot currently see as a comprehensive solution in the German government’s long-term scenarios. Heat pumps, preferably operated with PV systems on your own roof, remain the first choice for climate-friendly heating in many homes. This is particularly efficient and cost-effective in well-insulated new buildings. Heat pumps also work in older buildings: however, the flow temperatures required for conventional heating systems make the heat pump less efficient. This means that heating with a heat pump can often be more expensive than before. In the end, the price ratio of electricity and hydrogen will be decisive for H2 heating systems – and how much hydrogen will be left over for private heating at all after the major requirements for the decarbonization of industry. But whether hydrogen or heat pumps: in areas with a high population density, it is often better to think about heating for an entire neighborhood rather than for individual single-family homes. Implementing the heating transition in practice is a major challenge in many respects – but one that is worthwhile!”

Dr. Noah Pflugradt, Jülich Systems Analysis (ICE-2), Forschungszentrum Jülich

How safe is hydrogen?

Thomas Grube: “In short, hydrogen is safe to use for end consumers. What distinguishes this energy carrier from others: When hydrogen mixes with oxygen, it quickly becomes a highly flammable gas. I often hear that there is uncertainty among the population – because many people still know very little about hydrogen. We have long been familiar with other, equally flammable energy sources such as petrol or natural gas in everyday life, and people have no qualms about getting into a car with a petrol tank or heating it with gas. Fuel cell cars, for example, also have advantages in terms of safety. In the event of an accident, for example, it is almost impossible for their hydrogen tanks to break. Because they have to withstand the 700 bar pressure of the gaseous hydrogen, they are designed to be incredibly robust. Should a leak occur in the tank despite everything, the H2 would not accumulate under the vehicle like petrol or diesel, for example, but would disperse rapidly into the air – and would therefore be harmless at the scene of the accident. If it were to ignite, it would burn right at the point of release. In fact, there are currently even greater problems with battery-powered vehicles that catch fire, as significantly more extinguishing water is required to fight the fire and cool the battery, and batteries can catch fire again over a longer period of time.

This is not the case with hydrogen. Incidentally, the significantly higher drive efficiency of both battery and fuel cell vehicles means that much less energy is stored in the vehicle than in today’s cars with combustion engines. The potential risk is therefore much lower.”

Dr. Thomas Grube, Jülich Systems Analysis (ICE-2), Forschungszentrum Jülich

How can hydrogen be used in mobility?

Hydrogen cars

In fact, most battery-powered electric cars are significantly more efficient in everyday use than fuel cell cars. These, in turn, have a significantly greater range of around 600 to 700 kilometers. Hydrogen cars can therefore make perfect sense for longer vacation trips or for company representatives in the field. There are currently around 2,000 hydrogen-powered cars and around 100 hydrogen filling stations in Germany. Incidentally, the price of a full tank of gaseous hydrogen (around 5 to 6 kilograms) is currently slightly more expensive than for a comparable diesel vehicle. So far, however, no fuel tax has been levied on hydrogen. Should this change in the future, hydrogen costs would have to fall significantly to reach comparable fuel prices.

Hydrogen buses

Several hydrogen-powered buses are already in operation on the Jülich campus. Hydrogen buses perform better than electric buses, especially on longer overland routes – as well as on hilly terrain, where electric buses quickly run out of breath. On the other hand, electric buses are more effective in normal city traffic with flat routes.

Hydrogen truck

The first trucks with fuel cells have been driving on German roads since November 2022. Even though more hydrogen trucks are gradually coming onto the market, they are still in the market launch phase.

Hydrogen tractors and construction machinery:

Here, manufacturers are investigating – in some cases together with Jülich institutes – whether hydrogen drives can be more economical than battery or e-fuel drives.

Hydrogen ships

So far, these have only been used on a very small scale, for example as passenger ferries in Norway or push boats in the Berlin area. However, the first pilot projects with hydrogen-powered cargo ships are planned for the coming years.

Hydrogen airplanes

Large long-haul aircraft powered by green hydrogen would be a boon for the climate. However, this is not likely to happen in the foreseeable future. The problem is the high energy requirements of the engines: the hydrogen tanks would be far too large for these heavy aircraft. Development will probably take another 20 to 30 years. Smaller aircraft could be ready for the market much sooner, with Airbus planning its first commercial aircraft for 2035. eFuels produced from green hydrogen could be a good interim solution for larger aircraft.

Hydrogen trains

Dr. Julian Kadar, Helmholtz Institute Erlangen-Nuremberg for Renewable Energies (IET-2)

The Helmholtz Institute Erlangen-Nuremberg for Renewable Energy (HI ERN) is working closely with industrial partners to demonstrate that trains can be effectively fuelled with hydrogen. The planned train is to be fuelled with the liquid hydrogen carrier LOHC, which has safely bound the hydrogen. The hydrogen, which can be released over long distances, will then be used to power the locomotive electrically via a PEM fuel cell. ‘Especially for long-distance transport, hydrogen stored in LOHC offers a much greater range than batteries,’ says Dr Julian Kadar. ‘Many train routes in Germany do not have an overhead electric line, and a comprehensive conversion would be expensive and complex.’ At the same time, existing diesel tanks could continue to be used for the LOHC liquid. ‘This means that no completely new infrastructure needs to be built, as would be necessary for gaseous hydrogen.’ The aim is to operate locomotives in this way in a pollutant-free and, with green hydrogen, CO2-neutral way.

The copyright for the images used on this website is held by Forschungszentrum Jülich, aligator kommunikation GmbH and

stock.adobe.com.