X-rays play a special role in Peter Walter’s life. Because of them, the physicist with a doctorate moved to Forschungszentrum Jülich last summer. There, at the Institute for a Sustainable Hydrogen Economy (INW), he is leading the construction of a unique research instrument – a large-scale sample environment for an X-ray beamline. That sounds complicated – and it is. We’ll explain later. The new facility is being created as part of a team: to make it happen, Peter Walter is setting up the Department of Long-Term and High-Throughput Characterization in the Institute Division of Catalytic Interfaces (INW-1) under Professor Hans-Georg Steinrück.

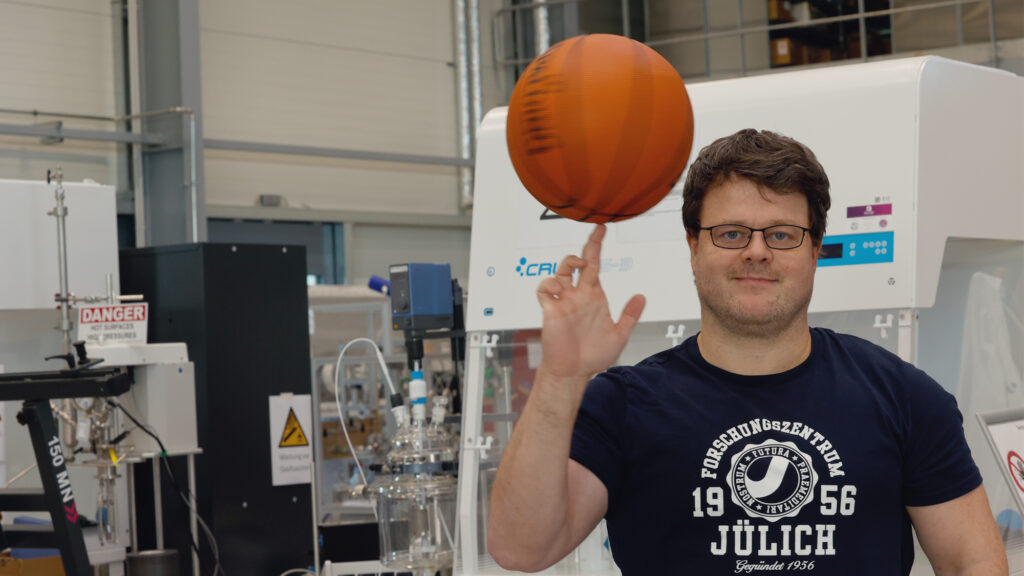

His first fateful encounter with X-rays in 1997 was unintended. Back then, he wanted to become a professional basketball player. With his team KICKZ München Basket, he had won the Bavarian A-Youth Championship the previous year. As point guard – or in non-basketball terms playmaker – he directed the game until a serious shoulder injury ended his career. One X-ray image made that unmistakably clear.

A Plan B That Wasn’t One

Plan B was to train as a technical draughtsman. “It soon became clear to me that this wasn’t something I could do for the rest of my life,” says Peter Walter today. So he looked for a new Plan A: the young man, who held a lower secondary-school certificate at the time, went back to earn his Abitur (university entrance qualification) and then studied Technical Physics in Berlin.

At the German Electron Synchrotron (DESY) in Hamburg, Peter Walter subsequently worked as a beamline engineer on the construction of an X-ray beamline. The starting point was an empty hall; the long-term goal was a hall filled with beamlines.

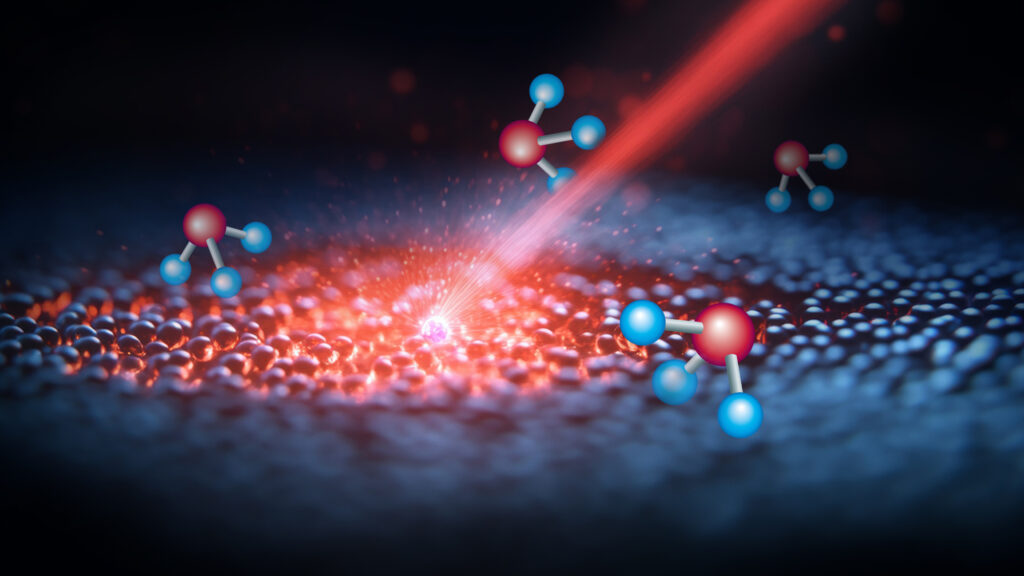

With a beamline, scientists study structures at the atomic and molecular level by directing X-rays through optics that focus them and then onto samples. The resulting scattering patterns reveal the position and condition of the smallest particles – a foundation for many physical insights.

During this time, Peter Walter also earned his PhD in physics at RWTH Aachen University. Afterwards, he continued working at DESY as a postdoctoral researcher.

A Very Special Cookie Box

At DESY, an X-ray beamline is connected to a synchrotron – a particle accelerator that, among other things, generates intense X-rays. Shortly after arriving in Hamburg, Peter Walter knew: “Building large research instruments – that’s exactly my thing.”

Since then, he has worked on many large-scale projects. Describing them all would be like trying to fit a multi-tiered wedding cake into a biscuit tin. Speaking of biscuit tins – or “cookie boxes”: that is the nickname of the Multi-Resolution Electron Spectrometer Array that Peter Walter conceived and built for the first time during his time in Hamburg. The measuring instrument can operate in parallel with other experiments without disturbing the beam.

A Million Flashes per Second

Walter later moved to the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory at Stanford University, which specialises in particle accelerators, X-ray lasers and materials research. He continued to develop the “cookie box” idea there. It was also at SLAC that he met Hans-Georg Steinrück – a connection that would later influence his move to Jülich. At SLAC, he worked on the Linac Coherent Light Source (LCLS), the world’s first X-ray free-electron laser.

From 2017 to 2022, Walter led the planning and construction of a beamline for LCLS II, an upgraded version of the first X-ray free-electron laser, capable of producing up to one million X-ray pulses per second instead of 120. The higher repetition rate posed a challenge for the mirror systems – and for the entire team. “After years of planning and design, we started construction right in the middle of the pandemic – in an empty hall – and built a one-of-a-kind measuring instrument,” he recalls.

Just as in basketball, a playmaker only functions as part of a team. The same holds true for a playmaker with an international reputation. Before joining Jülich, Peter Walter was the lead author of the FEL Roadmap, which paved the way to unravel chirality in the gas phase. The topic sounds complex but is fundamental to our understanding of molecules, reactions, and even life itself.

Chirality means that many molecules are identical in structure yet behave differently as mirror images. For example, they can bind to different molecular partners – comparable to a left and a right glove, which each fit only the corresponding hand. A familiar example is the so-called left-handed and right-handed yoghurt cultures. The human body can easily process the left-handed ones, whereas it excretes the right-handed ones unprocessed.

Peter Walter also relies on teamwork in Jülich. The planned beamline with its large sample environment will enable a substantial number of long-term experiments to be conducted in parallel. Each sample is sealed and equipped with an autonomous infrastructure, allowing reactions within to proceed continuously without interruption. “We are building an environment in which numerous samples can react over extended periods. Every day, they are exposed to the X-ray beam and measured to monitor their structural and chemical changes,” he explains. This approach makes it possible, for example, to identify the causes of activity losses in catalysts – and to explore strategies to mitigate them.

Faster from X-ray Technology to Application

Constructing such a large-scale facility takes years, yet Peter Walter’s anticipation is high. “For more than 20 years I did fundamental research without a direct application link. Here at INW I can now conduct application-oriented basic research. Knowing that the results of our work can be implemented directly was a strong argument for returning to Germany.”

At INW, four Institute Divisions work closely together: INW-1 studies atomic processes, INW-2 develops catalyst materials, INW-3 designs reactors, and INW-4 plans entire chemical plants. Each Division’s work builds on the others. The success of a new large-scale facility begins with new insights into changes at the atomic level.

Peter Walter aims to use a method from fundamental research – X-rays – to enable direct applications, such as longer-lasting catalysts that store hydrogen more efficiently in molecules like methanol or ammonia. This makes hydrogen as an energy store more practical and more affordable. “I have always enjoyed building large instruments that help us understand and exploit phenomena on the smallest scales,” he emphasises.

Now he is building novel X-ray beamlines that will drive the energy transition forward. And he is doing so in a very special team. Every individual is an indispensable part of a team, and every team is indispensable to the mission of the entire institute. It is, in a way, teamwork2.

Graphic: Adobe Stock

The copyright for the images used on this website is held by Forschungszentrum Jülich, aligator kommunikation GmbH and stock.adobe.com.